Here, we discuss how to brief a case for law school. However, before we get into those, it is necessary to lay the groundwork and a few principles.

Briefing cases is a great way to critically read the facts, closely read the cases, and prepare for class discussion.

However, you do not have to handwrite a brief for every case you are assigned in order to do well. It is more important to incorporate case preparation into an overall study strategy like this.

However, briefing cases is not a bad skill to have . . .

Briefing cases can be helpful. Briefing cases helps you become detail-oriented and it is helpful for dissecting somewhat complicated fact patterns. It helps you to remain focused when you read. Perhaps it makes you less nervous if you’re called on. Briefing cases also helps you get comfortable with legal language if you regularly put the facts and law into your own words when writing your case briefs. Briefing cases can help you truly dissect and understand the case. It can help you extract key legal rules. And think like a lawyer.

I found that dissecting the actual language of the case was more important. So I recommend, in general, to stick to book briefing, which is a form of case-briefing (which does not involve rewriting full case briefs) which we will discuss below.

A lot of students who choose to brief cases end up practically writing the whole case over again. This is oftentimes because they:

That brings us to the third principle.

Case briefs should be written in your own words. They should be written after you have personally spent a lot of time reviewing the case (so you should read the case at least once through before starting on your case brief).

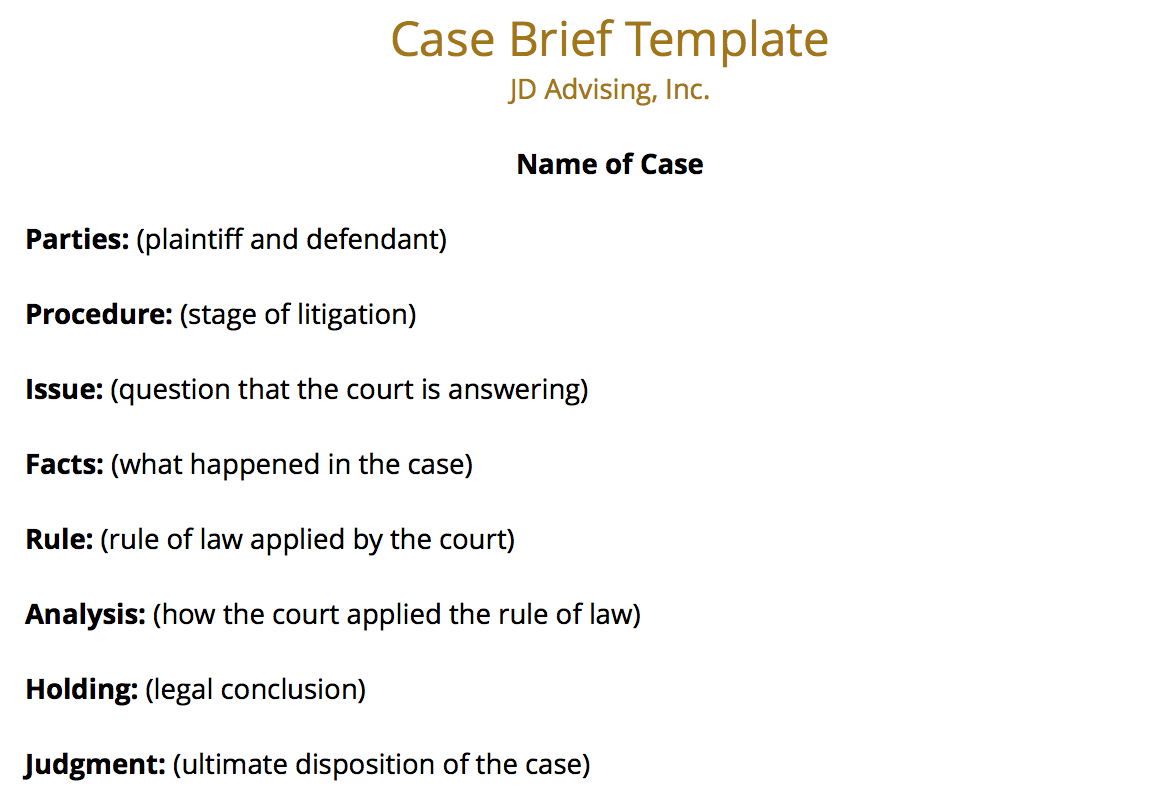

Before we dive into a step-by-step guide to briefing cases, let’s look at a case brief template. This template tells you the general parts of a case brief.

These “basics” don’t have much bearing on the substances of the case (the exception is that the procedural history may matter in a Civil Procedure class).

Rather, these basics are just the basic tools that will help you identify what the case is called, who the parties are, and where, in the court system, the case is.

Start by saying the name of the case at the top of your case brief—for example, Smith v. Jones.

Identify the parties. Who is the plaintiff? The defendant? Once you identify who’s who, you might want to abbreviate the parties as “P” and “D” to make it easier and quicker to write your brief.

Identify the procedural posture of the case. Are we at the trial or appellate level? State or federal court? At which stage in the litigation was the case when the issue arose?

Step Two: Identify the issue:

Identify the legal issue that the opinion is addressing. Often, the cases assigned in a casebook are shorter excerpts of a much longer opinion, so the issue will be apparent.

A trick to figure out the issue: Look at where in the casebook the issue is presented (e.g., if it is being presented under “breach of duty”, then the issue probably has to do with breach of duty)

The keyword here is relevant. Case opinions will typically include a detailed story about what happened. Your goal is to distill it down into the most relevant facts. For example, if a Torts case focuses on whether the defendant had the intent to commit a battery, facts such as the medical expenses incurred would not be relevant. But facts about the plaintiff and the defendant’s relationship (that may indicate the presence of intent, or lack thereof, may be relevant).

So don’t write all the facts down! Instead, write down the legally significant facts.

The next step is to state the rule that the court applied. Remember to not summarize the rule. Instead, you will likely want to copy it exactly as the court states it. (Every word can make a difference in how the law may be applied!)

Note that a court might be applying a well-established rule or it may be fashioning its own rule.

Next, describe the court’s reasoning. Which facts did the court apply the rule of law to? (These facts should also be in your factual summary, above!)

If the court developed a new rule of law after viewing a case of first impression, then why did it choose to do so? Did it rely on specific facts? Public policy? A court opinion from a higher court?

This is the court’s legal conclusion. For example, did the court hold that the defendant was liable for negligence? The holding is basically the outcome of the case. It is what happens when the court applies the rule of law to the facts.

This is the ultimate disposition of the case. Did the court grant or deny a motion? Affirm or reverse a lower court? The judgment can usually be just a few words at the end of your case brief.

Note that some case briefs combine the judgment with the holding under the “holding” section of the case brief.

Step Seven: If there is a dissenting or concurring opinion, it may be worth it to jot a few notes on it.

Not every case has a dissenting opinion or concurring opinion, but if your casebook includes one, it’s not an accident. Oftentimes, a dissent can be just as important as a majority opinion, especially if it highlights a major disagreement in the law or points out significant gaps in the majority’s reasoning. Further, there’s a good chance that your professor will want to discuss it. In short, jotting down one or two sentences about the dissent or concurring opinion can be valuable in preparing you for class discussion.

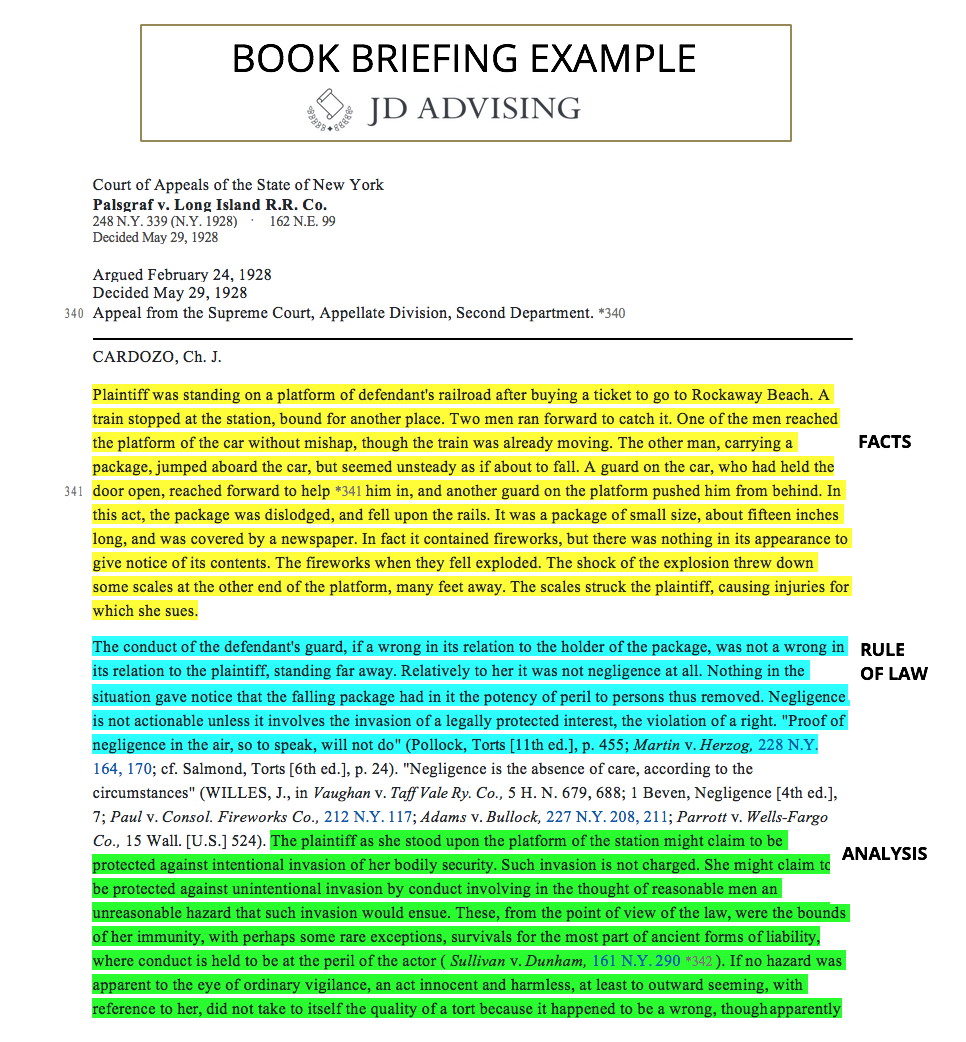

We recommend book briefing. Book briefing is essentially a heavy annotation of a case in the casebook—i.e., you identify the key portions of the case, and you add notes in the margins to aid you during class and in your studying.

An example is below:

The nice thing about book briefing is you still closely read the case, you just don’t spend valuable time rewriting large portions of the case. And, you can look at your casebook if you are called on in class and you have everything you need—your notes, as well as the case—in one place.

Every student learns at their own pace and uses case-briefing and book-briefing differently in their overall study plan.

We hope this gives you some guidance as you begin to brief cases in law school! Good luck!

By using this site, you allow the use of cookies, and you acknowledge that you have read and understand our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

We may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

Essential Website CookiesThese cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

Check to enable permanent hiding of message bar and refuse all cookies if you do not opt in. We need 2 cookies to store this setting. Otherwise you will be prompted again when opening a new browser window or new a tab.

Click to enable/disable essential site cookies. Other external servicesWe also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Click to enable/disable Google Webfonts.Google Map Settings:

Click to enable/disable Google Maps.Google reCaptcha Settings:

Click to enable/disable Google reCaptcha.Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

Click to enable/disable video embeds. Privacy PolicyYou can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

We are using cookies to give you the best experience on our website.

You can find out more about which cookies we are using or switch them off in settings .